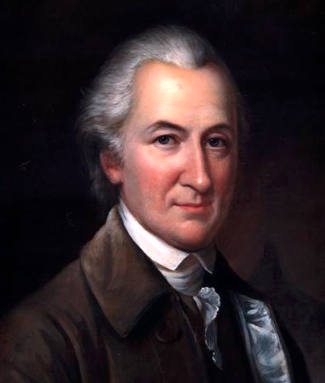

1732 – 1808

John Dickinson, “Penman of the Revolution,” was born in 1732 at Crosiadore estate, near the village of Trappe in Talbot County, Maryland. He was the first son of Samuel Dickinson, the prosperous farmer, and his second wife, Mary (Cadwalader) Dickinson. In 1740, the family moved to Kent County near Dover, Delaware, where private tutors educated the youth. In 1750, he began to study law with John Moland in Philadelphia. In 1753, Dickinson went to England to continue his studies at London’s Middle Temple. Four years later, he returned to Philadelphia and became a prominent lawyer there. In 1770, he married Mary Norris, daughter of a wealthy merchant. The couple had two daughters.

By that time, Dickinson’s superior education and talents had propelled him into politics. In 1760, he had served in the assembly of the Three Lower Counties (Delaware), where he held the speakership. Combining his Pennsylvania and Delaware careers in 1762, he won a seat as a Philadelphia member in the Pennsylvania assembly where he remained through 1765. He became the leader of the conservative side in the colony’s political battles. His defense of the Quaker charter against the faction led by Benjamin Franklin earned him respect for his integrity and Franklin lost his seat in the assembly.

In the meantime, the struggle between the colonies and the mother country had waxed strong and Dickinson had emerged in the forefront of Revolutionary thinkers. In the debates over the Stamp Act (1765), he played a key part serving as de facto leader of the Stamp Act Congress and authoring its publications. Later that year, he wrote The Late Regulations Respecting the British Colonies… Considered,an influential pamphlet that urged Americans to seek repeal of the act by pressuring British merchants.

In 1767-68, in response to the Townshend Duties, Dickinson wrote a series of newspaper articles entitled “Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania.” They attacked British taxation policy and urged resistance to unjust laws, but also emphasized the possibility of a peaceful resolution. So popular were the “Letters” in the colonies that Dickinson received an honorary LL.D. from the College of New Jersey (later Princeton), public thanks from a meeting in Boston, accolades from around the colonies, and international celebrity. He championed rigorous colonial resistance in the form of nonimportation and nonexportation agreements and peaceful means of resistance, including civil disobedience.

In 1771, Dickinson returned to the Pennsylvania legislature and drafted a petition to the king that was unanimously approved. He particularly resented the tactics of New England leaders in that year and refused to support aid requested by Boston in the wake of the Intolerable Acts, though he sympathized with the city’s plight. In 1774 he chaired the Philadelphia committee of correspondence and briefly sat in the First Continental Congress as a representative from Pennsylvania. He authored four of the six documents published by Congress.

Throughout 1775, Dickinson supported American rights and liberties, but continued to work for peace. He drew up petitions asking the king for redress of grievances. At the same time, he chaired a Philadelphia committee of safety and defense and held a colonelcy in the first battalion recruited in Philadelphia to defend the city.

After Lexington and Concord, Dickinson continued to hope for a peaceful solution. In the Second Continental Congress (1775-76), still a representative of Pennsylvania, he drew up the Olive Branch Petition and the “Declaration of the Causes of Taking Up Arms.” In the Pennsylvania assembly in November 1775, he drafted instructions to the delegates to Congress directing them to seek redress of grievances, but ordered them to oppose separation of the colonies from Britain. In June 1776, he wrote new instructions allowing them to vote for independence, but not expressly instructing them to do so.

By that time, Dickinson’s moderate position had left him in the minority, but he nevertheless was asked to draft the Articles of Confederation. In Congress, he abstained from the vote on the Declaration of Independence (1776) and refused to sign it. Nevertheless, he then became one of only two contemporary congressional members (with Thomas McKean) who entered the military. During the summer, while on the New Jersey front, he was voted out of the Pennsylvania assembly. When much of his unit deserted, he resigned his colonelcy and accepted reelection to the Pennsylvania assembly in the fall of 1776. When the revolutionary government would not consider amending the new constitution to protect dissenters’ rights, he resigned his seat. He then enlisted as a private in the Delaware militia and may have taken part in the Battle of Brandywine, Pennsylvania (September 11, 1777). He was given a commission as brigadier general in the Delaware militia, but he appears not to have acted on it.

Dickinson took a seat in the Continental Congress (1779), where he signed the Articles of Confederation, although a much different version from the one he had drafted. In 1781, he became president of Delaware’s Supreme Executive Council. Before his tenure was over, he was elected president of Pennsylvania (1782-85). In 1786, representing Delaware, he attended and chaired the Annapolis Convention and authored the letter to Congress calling for the Constitutional Convention.

The next year, Delaware sent Dickinson to the Constitutional Convention. He missed a number of sessions and left early because of illness, but he made worthwhile contributions, including engineering the solution for representation known as the Connecticut Compromise and arguing for the end of the slave trade. Because of his premature departure from the convention, he did not actually sign the Constitution but authorized his friend and fellow-delegate George Read to do so for him. From home he wrote the Fabius Letters (1788) arguing for ratification.

Dickinson continued to be active in public affairs. In 1792 he served as president of the Delaware Constitutional Convention, in 1795 he led citizen opposition to the Jay Treaty, and he served as informal advisor to politicians, including Senator George Logan, Attorney General Caesar A. Rodney, and President Thomas Jefferson. In addition to continuing to publish pamphlets on current events, in 1801 he published two volumes of his collected works. He died at Wilmington in 1808 at the age of 75 and was entombed in the Friends Burial Ground.

(Return to Gallery of Founding Fathers)